How Does the Beard Make the Man?

An Article by James Polchin for BEARDS OF NEW YORK, the photo book

On a cool morning in October of 1839, bearded Robert Cornelius set up his crude camera in the back of his father’s lighting store in Philadelphia. Cornelius was a student of chemistry and he was fascinated with the mixture of chemicals, light, and patience required to produced a new form of image making called photography.

Sitting still for over five minutes in front of the open lens, Cornelius took his portrait—what was known then as a daguerreotype after its French inventor Louis Daguerre. After a series of chemical washes and a long drying process, the image appeared. Cornelius’s portrait is quiet a clear image. Looking a bit of a dandy, he stares intently at us, his hair disheveled, his jacket collar pulled up close around his neck. What is also clear is the outline of his beard that grew along his jaw line, and converged at the tip of his chin.

This was not just any portrait. This was the first photographic portrait ever recorded. And the first photographic portrait was of a bearded man.

Looking at the origins of photography you will find an archive of bearded men. By the middle of the 19th century in most large cities in Europe and America, photographic studios emerged to cater to the growing middle classes. Men and woman were thrilled to have their portraits taken, often posing with well upholstered chairs or heavy tables, their layers of clothing as much on display as their faces. These portraits were turned into playing-card sized photographs called carte de visite. Clients would order hundreds of them to pass out as their personal calling cards.

The men in these portraits are overwhelmingly bearded, with a vast array of whisker shapes and styles that would amaze even today’s most fashionable hipster. The Victorian beard often indicated not only style but class and gender as well. In an age when men and women occupied very different spheres in public and private life, the beard was the ultimate expression of masculinity, a symbol of sexual vigor, and a marker of authority and success. Many advocates of the male beard cited its health benefits in preventing diseases of the mouth and the throat. As so often happens with the beard, function follows form.

But the 19th century was just one very hairy moment in the rise and fall of the male beard. From the ancient Egyptians and Greeks to our modern era, the beard has often meant more than facial hair, standing as a paradoxical symbol of class privilege or servitude, religious devotion or blasphemy, political revolutionary or social conservative.

King Henry VIII imposed a beard tax in the 1500s, capitalizing, one might assume, on the dominant style that his own beard helped to inspire. As a way of looking more Western, Peter the Great did the same thing in Russia nearly two centuries later. Look at any portrait of the emperor and he sports only the dashing moustache without a hint of beard. By the 18th century, among the upper classes of Europe, the beard was shunned as a sign of madness or demonical vices. As beard historian Allen Peterkin has noted, when the beard began its return in the early 19th century, many thought it was messy and “concealed the ‘true face,’ thus protecting criminals and the morally inferior.” In a more recent era, the metaphor of “the beard” would be a colloquial term to describe female companions of gay men: the woman’s presence providing a public, heterosexual image for the often well groomed and well shaved man.

In the early 20th century, the modern man favored the clean-shaven look, casting aside the beard as a relic of Victorian ideas. A smooth face was the preferred look of authority and style (thanks in part to the invention of disposal razors and electric shavers). So it is no surprise that by the middle of the last century the bearded man was at best an image of a nonconformist, at worst a madman, anarchist, or revolutionary. Think of Che Guavara’s and Fidel’s Castro’s solid beards of the 1960s, symbols not only of their masculine strength but also their revolutionary ideas. Consider Beat poet Allan Ginsburg’s ragged whiskers, Malcolm X’s well trimmed goatee, John Lennon’s wispy beard, or the hippies’ unkempt ones. There is a wonderful irony here, for as much as a beard might confirm the image of a strong leader, it can also be a rejection of social norms altogether. At mid-century, the male beard was a symbol of the social outsider, angry rebel, and the sexually liberated.

Echoes of those earlier ideas are certainly seen in the contemporary resurgence of the beard. But terms like hipster and lumbersexual float around as marketing and media labels more than actual personal identities. The beard today is caught in a paradox between social statement and commodity, between identity and the marketplace. The men who sport beards are for the most part not starting revolutions or building communes in the mountains. Instead, they are entrepreneurs and actors, finance managers and programmers, CEO’s and bankers.

As in the past, the beard confirms something authentic and genuine about masculinity today. While it may conjure a “back to nature” image, it also is anchored to our ideas of beauty. The host of products aimed at the stylish beard, articles on beard maintenance, and the rise of specialty beard salons all attest to the contemporary beard’s ultimate paradox: a symbol of both the natural man and the highly fashionable one. This paradox also points at the open secret we all known but tend to ignore: there is nothing authentic about masculinity. The history of the beard, our love/hate relationship with men’s whiskers, reminds us of this fact.

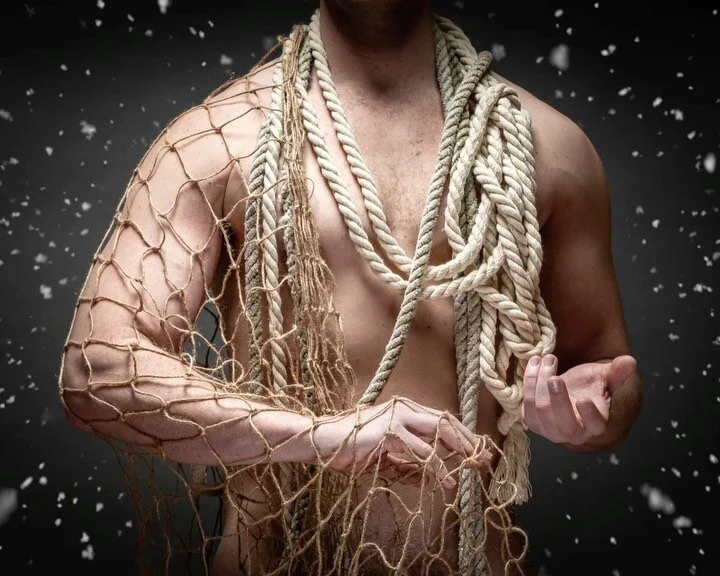

In capturing the beauty and variety of the modern beard in all its shapes and sizes, these 101 beards recall those 19th century images of men posing with dignity, pride, and conceit. But this collection is of its time and era as much as it comments upon it. Poised in front of the stark pink background and dusted with glitter, these men present a complex and playful image of contemporary masculinity. These photographs ask: How does the beard make the man?

The history of the beard offers an answer: it’s complicated.

James Polchin is a writer and academic living in New York. He holds a Ph.D. in American cultural history, and teaches courses in writing and visual cultures in the Liberal Studies program at New York University.